The Twenties

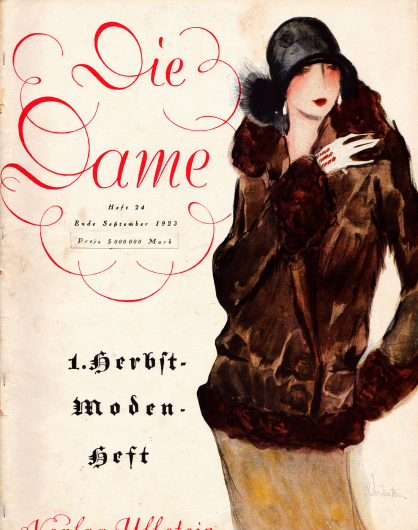

Cover of the German magazine Die Dame (Fall Fashion Issue) in the heyday of hyperinflation at the price of 5 million marks — Die Dame, no. 24 (50), Last September Issue 1923. Illustrator: Julie Haase-Werkenthin (1882-1960)

Cover of the German magazine Die Dame (Fall Fashion Issue) in the heyday of hyperinflation at the price of 5 million marks — Die Dame, no. 24 (50), Last September Issue 1923. Illustrator: Julie Haase-Werkenthin (1882-1960)

In the 1920s fashion changed radically. But this change was no coincidence, but the result of a drastic social upheaval. Above all, the impression of the First World War brought irreversible upheavals that created a completely different zeitgeist. In the twenties the past ideas of morality eroded. They were replaced by new ideas, which at the same time marked the dawn of modernity as we understand it today.

Political and Economic Crises

Film actress Peggy Longard in a summer costume with a vest tied at the side and a sports costume — Elegante Welt, no. 11 (10), May 1921, p. 9; Chicago Mail Order Co., Spring/Summer 1922, p. 2C. Photo (left): Ernst Sandau

Film actress Peggy Longard in a summer costume with a vest tied at the side and a sports costume — Elegante Welt, no. 11 (10), May 1921, p. 9; Chicago Mail Order Co., Spring/Summer 1922, p. 2C. Photo (left): Ernst Sandau

Ladies' hats of silk taffeta, hemp and various straws. Rooster and ostrich feathers, wool embroidery, silk flowers and pleated rosettes of grosgrain ribbon serve as ornaments

—

Chicago Mail Order Co. Spring/Summer 1922, p. 2

Ladies' hats of silk taffeta, hemp and various straws. Rooster and ostrich feathers, wool embroidery, silk flowers and pleated rosettes of grosgrain ribbon serve as ornaments

—

Chicago Mail Order Co. Spring/Summer 1922, p. 2

After the catastrophe of the First World War, the world was not the same as before the war. The old European order was irrevocably disintegrating. More than 10 million soldiers from all warring parties had fallen or were missing, twice as many had become invalids as a result of the war. Europe had lost its political supremacy in the world and was economically ruined. Northern France and Belgium were devastated by the four-year war. Supply shortages continued well beyond the end of the war in November 1918 and the political map of Europe was completely reshaped by the Peace of Versailles in June 1919.

While the October Revolution in 1917 brought the communists to power in Russia, the new independent Austria became a parliamentary democracy. After the abdication of Emperor Wilhelm II in 1918, Germany also became a democracy, but it was politically extremely unstable. The Weimar Republic was shaken by crises and coups d'états, and only after the hyperinflation of 1923 did it experience a phase of relative economic and political calm. Less weakened but heavily indebted as a result of the war were also the supposed victorious countries Great Britain and France.

Only the United States seemed to emerge strengthened from the Great War.1 The rising industrial nation was no longer established on the world stage as a mere economic but now also as a significant political power. But also the USA experienced troubled times after the war through strikes and riots. The high inflation caused by the war was only stopped by the collapsing demand from 1919. This was followed by a drastic fall in prices, which plunged the US economy into a severe recessionary phase that did not peak until 1920/21.

First World War as Culture Shock

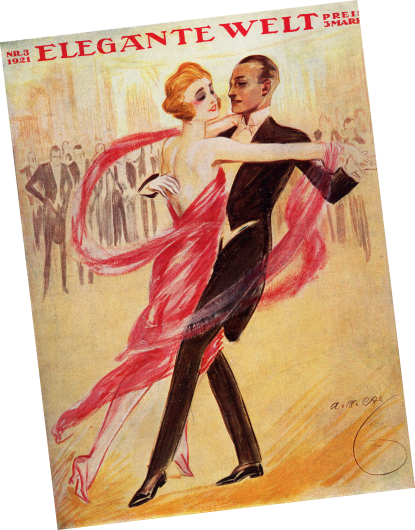

Elegante Welt introduced the Shimmy and the Scottish Espagnole in 1921 at the height of the dance craze — Elegante Welt, no. 3 (10), February 2, 1921. Cover: A. M. Cay (1887-1971)

Elegante Welt introduced the Shimmy and the Scottish Espagnole in 1921 at the height of the dance craze — Elegante Welt, no. 3 (10), February 2, 1921. Cover: A. M. Cay (1887-1971)

In addition to political earthquakes and economic turbulence, the World War left behind a traumatized society that was robbed of many illusions by the misery and cruelty of war. The catastrophe of the world war, which in retrospect was also declared as the "primeval catastrophe of the 20th century"2, had an effect as enormous culture shock and shook the world view of a whole generation lastingly. This caesura in the history of the 20th century led in many areas to a radical break with the past and gave impetus to new ways of thinking and currents that were already slowly developing before the war. Architects and artists broke with historical traditions and sought new forms of expression appropriate to the times. Literature, theatre and the young medium of film broke new ground and tried to come to terms with the trauma of war.

The end of the war was perceived with great relief throughout Europe and overseas. The feeling of having survived and survived the war with all its hardships, efforts and horrors awakened an enormous zest for life in an entire generation. A feeling of "Oops We Live!"3 determined above all the immediate post-war period. After years of everyday hardship, uncertainty and privations one wanted to enjoy oneself again unabashedly and looked for diversion and entertainment of any kind. The dance enthusiasm was enormous, many dance events were completely overcrowded. Cabarets, variety theatres, theatres, opera houses, pubs and cinemas experienced a real boom after the war, which remained unbroken in the following years. Especially the end of the public dance ban in the German Reich on New Year's Eve 1918/19 led to a real dance wave, despite the politically explosive situation in Germany:

"The air is like electrically charged, a political high voltage without equal. The floor of Berlin is glowing. This is how the old year has come to an end: in feverish excitement, and it seems as if one knew of nothing else but the seriousness of the hour. But already the confetti of carefree New Year's Eve brothers is drawing its snakes, and life-hungry men and girls are dancing into the New Year. The music is played in hundreds of venues. Dances over dances, waltzes, fox trot, onestep, twostep, and the legs race as if bewitched over the hall floor, the skirts fly, the breath chases. Berlin has never seen such a New Year's Eve.4

Europe in Jazz Rhythm

The famous violinist Dajos Béla entertained the parties of the Berlin Adlon Hotel with his dance orchestra at the end of the twenties — Elegante Welt, no. 5 (18), March 4, 1929, p. 46. Photo: Studio Ernst Schneider, Berlin (1881-1959)

The famous violinist Dajos Béla entertained the parties of the Berlin Adlon Hotel with his dance orchestra at the end of the twenties — Elegante Welt, no. 5 (18), March 4, 1929, p. 46. Photo: Studio Ernst Schneider, Berlin (1881-1959)

In the early twenties, when skirt hems were still quite long, dark shades and opaque women's stockings were in fashion

—

National Cloak & Suit Co. Spring/Summer 1920, p. 291

In the early twenties, when skirt hems were still quite long, dark shades and opaque women's stockings were in fashion

—

National Cloak & Suit Co. Spring/Summer 1920, p. 291

With the American soldiers, new rhythms and the first jazz records came to Europe in 1917. After the end of the war, jazz also reached the German Reich via Great Britain and France. The first jazz record in Germany came onto the market in January 1920. Thus American culture conquered Europe for the first time. With the new music, new dances sloshed into Europe, which were an expression of a rediscovered joy of life and exuberant wildness. The shimmy took Europe by storm in 1920 and overtook the post-war Foxtrot and pre-war dances such as the Waltz and Tango. With the Charleston, the most popular fashion dance of the twenties was created in 1923, which originally came from the Broadway musical Runnin' Wild and was made famous in Europe in 1925, especially by Josephine Baker. The Black Bottom appeared on the dance floor in 1926, followed by the Lindy Hop in 1927.5

Especially the older generation, moral guardians and conservatives found the new dances particularly offensive and reprehensible, as they were, in addition to the stormy step sequences and the exstatic movements, sometimes extremely erotically charged. But the indignation did not stop the dance wave. The enthusiasm for dancing was also used by restaurants and hotels, which invited to the dance floor for 5 o'clock tea while jazz bands played the latest hits. Especially in health resorts and big cities, tea dance in the afternoon with lively dance music became a popular social event.

The Triumph of Film and Rise of Hollywood

The films, which were only a few minutes long at the beginning of cinema, developed from 1910 on into more and more elaborate and larger productions and finally became full-length entertainment. This development reached its first peak with the three-hour monumental work The Birth of a Nation by director D.W. Griffith in 1915. This filmic milestone established the reputation of the still young medium as a serious form of entertainment. The popularity of the young medium grew so fast that already in 1912 about five million Americans visited the national cinema theatres daily.6

During the First World War, the general cultural scene was subject to increasingly severe restrictions, while cinema offered a cheap alternative for a wide audience. For the United States, which was now cut off from European film productions that had previously dominated the American market, the war, initially limited to Europe, proved to be a great opportunity for the US film industry. The film studios, which had only moved from the East Coast to California from 1910 onwards due to better production conditions, were able to take advantage of the elimination of European competition and fill the gap that had arisen on the US market. Within a few years, the insignificant Hollywood near Los Angeles advanced to become the leading American film city and finally became the leading international film metropolis in the 1920s. In contrast, after 1918 the national European film industries could hardly continue the successes of the pre-war period. Europe had almost completely lost its supremacy in the film business as well.

Film as New Mass Medium

The splendor of old Europe in the US movie palace. Vestibule of an American movie theater — From: Fawcett, Welt des Kinos, Zurich et al. 1928, p. 78. Photo: Paramount

The splendor of old Europe in the US movie palace. Vestibule of an American movie theater — From: Fawcett, Welt des Kinos, Zurich et al. 1928, p. 78. Photo: Paramount

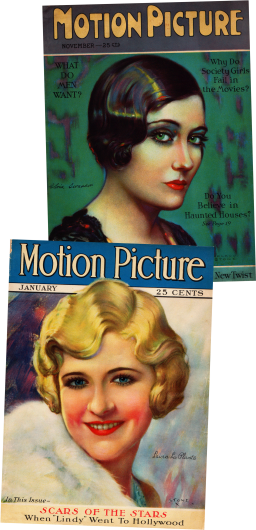

Cover pages of the U.S. movie magazines Motion Picture with movie stars Gloria Swanson and Laura La Plante (below) — Motion Picture, November 1926 and January 1928. Illustrator: Marland Stone (1895-1975)

Cover pages of the U.S. movie magazines Motion Picture with movie stars Gloria Swanson and Laura La Plante (below) — Motion Picture, November 1926 and January 1928. Illustrator: Marland Stone (1895-1975)

After the First World War, ever larger cinemas were built in all major cities in Europe and North America, offering visitors full-length entertainment and distraction from everyday life. From around 1912, the Nickelodeons of the turn of the century became ever larger cinemas with several hundred or even thousands of seats. American cinemas in particular became true movie palaces, whose sheer size as well as their pompous and extravagant decoration in various historical styles surpassed even most conventional theatres of the old world. Hollywood was not only a leader in the production of films. Of the 51,103 cinemas world-wide at the end of 1927, there were in the USA alone about 20,500 cinemas7 with a capacity of 18 million seats.8 4,300 cinemas were in the German Reich, 3,700 in England and 3,300 in France. Further 3,619 cinemas existed in Asia and 644 in Africa.9

Before the actual main films from Europe or Hollywood, small concerts of the orchestra or entertaining performances were shown on stage. This was followed by newsreels and supporting films such as comedies. Advertising and information films also took advantage of the increasing popularity of the new medium, which by the early twenties at the latest had developed into the most influential entertainment medium of all. While in Germany two million visitors daily visited the cinemas10, the number in the United States was over eight million daily.11 According to L'Estrange Fawcett in the whole year 1927 the cinemas worldwide counted six billion viewers, three billion of them alone in the United States.12

Film Stars as Fashion Icons

Two front pages of the New York City department store Hamilton Garment mail-order catalogs with portraits of Paramount stars May McAvoy (right) and Gloria Swanson — Hamilton Garment Co., Spring/Summer 1922 and Spring/Summer 1924

Two front pages of the New York City department store Hamilton Garment mail-order catalogs with portraits of Paramount stars May McAvoy (right) and Gloria Swanson — Hamilton Garment Co., Spring/Summer 1922 and Spring/Summer 1924

In order to satisfy the hunger of the millions of audiences for entertainment, hundreds of entertainment films were produced annually. Even before the twenties, the first audience favourites among the actors crystallized, whose films attracted the audience masses like magnets and increasingly surpassed and outshone the celebrities of the theatre stages of days gone by in popularity. Among the first international film celebrities of the still young medium were Henny Porten, Mary Pickford, Asta Nielsen, Lillian Gish and Pola Negri even before the First World War. Especially the big Hollywood studios such as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), Universal Studios, Paramount Pictures, Warner Bros., United Artists and Fox Film Corporation recognized and used the economic potential that could be achieved through a targeted image building and marketing of their mostly female actors.

Gloria Swanson became famous in 1919 with the movies Male and Female and Don't Change Your Husband directed by Cecil B. DeMille she became the first big Hollywood star of the silent movie era. Her extravagant film costumes, some of which were decorated with feathers and pearls, and her latest dresses attracted audiences in her heyday. Women all over the world emulated her glamorous role model and Gloria Swanson became Hollywood's first fashion icon. In the USA, advertisements and many mail order companies used the fame of the Hollywood stars, who were now popular far beyond the borders of the country, to bring the latest clothing to women. In the spring catalogue 1922 of the company Sears, at that time the largest mail order company in the USA, Gloria Swanson advertised Russian boots.13 The US mail order company Philipsborn's also advertised several times in its catalogues at this time with collections created exclusively by the famous ballroom dancer Irene Castle.

Patterns for Self-Tailoring

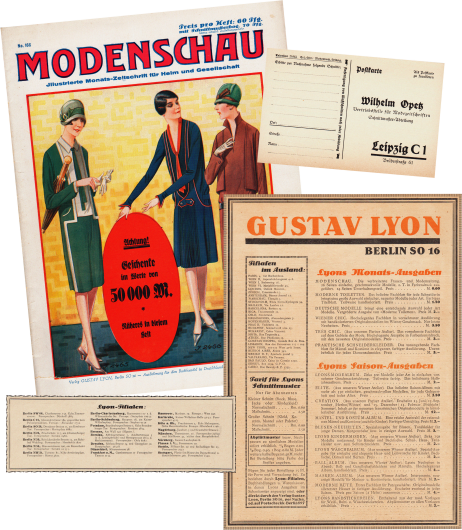

List of sales offices for patterns of publishing company Gustav Lyon in Berlin, Germany, and abroad for monthly and seasonal titles. Also available for order through Wilhelm Opetz, Leipzig (order form) — Modenschau, no. 166 (13), October 1926

List of sales offices for patterns of publishing company Gustav Lyon in Berlin, Germany, and abroad for monthly and seasonal titles. Also available for order through Wilhelm Opetz, Leipzig (order form) — Modenschau, no. 166 (13), October 1926

In the interwar period, the majority of fashion journals and handicraft magazines offered their readers, in addition to the fashion presented, the matching patterns, which could be more or less easily made at home on their own sewing machines or by a professional tailor. The leading distributor of patterns in Germany was the Berlin-based Ullstein Verlag, which published the fashion magazines Die Praktische Berlinerin and Das Blatt der Hausfrau. Both magazines were aimed primarily at the broad mass of German housewives. In contrast to it the magazine Die Dame die betuchte Frau von Welt, which appeared in the same publishing house, addressed the wealthy woman with the highest claim and exquisite taste.14

Ullstein offered matching patterns in six standard sizes for all models in the three publications and in other seasonal albums and catalogues. These patterns, which had been produced en masse as "Ullstein patterns" since 1912, could be ordered directly from the publisher by mail COD. Pattern samples were also sent to Austria, Switzerland and the Netherlands. In addition, the patterns could be purchased in the publisher's own sales offices and in another 1,000 department stores throughout the Weimar Republic.15 In 1927, publisher Ullstein proudly announced that it had established the pattern business in Germany and estimated that here alone some ten million dresses would be produced annually by self-tailoring.16

The large German market for patterns was shared by the Ullstein publishing house with the Gustav Lyon publishing house, also based in Berlin, and the Otto Beyer publishing house in Leipzig. Gustav Lyon published the magazines Modenschau, Moderne Toiletten, Deutsche Modelle, Wiener Chic, Très Chic and Praktische Schneiderkleider as well as nine seasonal fashion albums, some of which featured color illustrations. Normal patterns in standard sizes were sold as small cuts (skirts, blouses) for RM 0.60 or as large patterns (dresses, costumes) for RM 0.90 plus postage. For the price of RM 2.50, custom-made patterns for customers were also made. As with Ullstein, distribution took place through department stores, bookstores, a system of 24 sales offices throughout the Reich and by post.17 Otto Beyer Verlag published the monthly magazines Deutsche Modenzeitung, Beyers Modenblatt and, from 1929, die neue linie. The fabric required for self-cutting and tailoring could be purchased per yard in the large department stores, which had a wide range of different fabrics in the latest colors and patterns, or by mail order. Especially for lower and middle income groups the self-production of the clothes offered a good possibility to save money from the tight household budget.

The New Woman and the Fashion of the 1920s

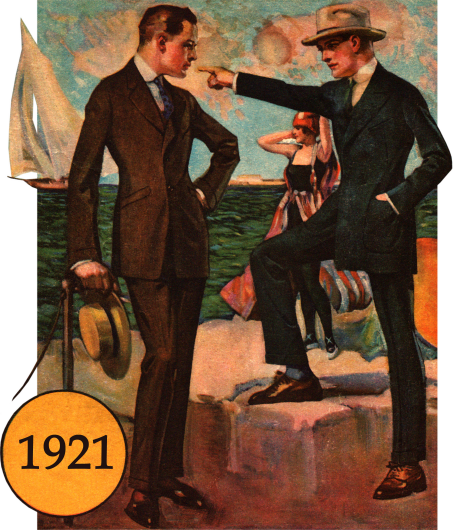

Men's fashion at the beginning of the twenties is extremely tightly cut. The jacket, similar to women's fashion, still shows a high and narrow waist and sloping shoulders

—

Philipsborns Spring/Summer 1921, p. 280

Men's fashion at the beginning of the twenties is extremely tightly cut. The jacket, similar to women's fashion, still shows a high and narrow waist and sloping shoulders

—

Philipsborns Spring/Summer 1921, p. 280

As early as 1918, fashion picked up on the pre-war period and skirts were cut tighter again at the lower legs - a brief revival of the hobble skirt, with the difference that the skirts were now worn slightly shorter. But many women didn't want to be pushed back into the old understanding of roles and the old fashion. The attempt of many designers to revive the opulent pre-war fashion found few followers. So the skirt hems became shorter and shorter year after year until 1922. Only for a short time in 1923/24 almost ankle-length skirts became popular again, but in the spring/summer season of 1925 they were shortened again: this time the skirt hem even went up to the knee. In fact, the new knee-short fashion only gradually gained acceptance in the following years until 1927.

The waist, too, began to drop from just below the chest from 1920 until 1925 to almost below the hip. Female contours disappeared in the straight line of the hanger dress. This created a very boyish and androgynous figure that seemed to try to suppress all femininity.

It was not until 1925 that the fashion we so often associate with the fashion of the 1920s became established: knee-short skirts and low waists - the typical flapper fashion. Characteristic for the fashion of the 2nd half of the 1920s was a certain uniformity and androgyny; the cut of the dresses was always very similar. Often the dresses only differed in details, for example in the colour combinations, the patterning of the fabrics, the fabrics themselves or their workmanship. THE fashion of the 20's did not even last 4 years. Already towards the end of the 20's figure-hugging dresses came back into fashion and the lost femininity was rediscovered.

From 1927 on, female forms were emphasized again and the waist returned to its natural position by autumn 1929. In 1927, extended skirt tips and sashes appeared in evening fashion, which again partially lengthened the skirt hems. In 1928 the Peacock Tail evening dress appeared, whose skirt was knee-short at the front but floor-length at the back. From 1929 on, this development also influenced the daily fashion which found its expression in one-sided or irregular skirt extensions. The hems of the skirts became successively longer again until the length of the skirt in daytime fashion in the autumn of 1929 was generally extended to below the knee and in evening fashion it was again floor-length. The new silhouette or princess fashion, as this new ladylike fashion line with its longer skirts and natural, tight waist was called, quickly displaced the sporty jumper and chemise dresses of the late 1920s.

Footnotes

1 In English-speaking countries, the term The Great War is still used today as a synonym for the First World War.

2 This assessment of the First World War goes back to the diplomat and historian George F. Kennan, who described it as "the great seminal catastrophe of this century". See also: Kennan, George F., The Decline of Bismarck's European Order. Franco-Russian Relations, 1875-1890, Princeton 1979, p. 3.

3 Title of a play by Ernst Toller from 1927.

4 N. N., untitled, in: Berliner Tageblatt, no. 1 (48), January 1, 1919, first supplement, quoted after: Glatzer, Ruth, Berlin zur Weimarer Zeit. Panorama einer Metropole 1919-1933, Berlin 2000, pp. 21-22.

5 An overview of the dances of the 1920s can be found on the website www.return2style.de under the heading "Museum". Goebel, http://www.return2style.de/homepage.htm [last accessed: October 8, 2014].

6 Mulvey, Kate; Richards, Melissa, Decades of beauty. The changing image of women, 1890s - 1990s, London 1998, p. 50.

7 Fawcett, L'Estrange, Die Welt des Films, Zurich, Leipzig, Vienna 1928, p. 79, translated, freely edited and supplemented by C. Zell and S. Walter Fischer. The complete statistics from the book can be found in the Wikipedia article on the history of cinema, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geschichte_des_Kinos [last accessed: June 19, 2015].

8 The capacity here refers to the year 1926. Fischer, Lucy, American Cinema of the 1920s. Themes and Variations, New Brunswick, N.J. et al. 2009, p. 15.

9 Fawcett, World of Film, p. 79, as note 7.

10 Scriba, Arnulf, Weimar Republic. Kunst und Kultur, in: https://www.dhm.de/lemo/kapitel/weimarer-republik/kunst-und-kultur.html [last accessed: September 18, 2015].

11 Figures on the number of daily visitors vary widely. While Lucy Fischer speaks of 100 million visitors per week in 1926, David E. Kyvig gives a figure of 65 million tickets sold in 1928. Fischer, Cinema, p. 15, as note 8; Kyvig, David E., Daily Life in the United States, 1920-1939. Decades of Promise and Pain, Westport, Conn. and others 2002, p. 80.

12 Fawcett, World of Film, p. 80, as note 7.

13 Blum, Stella, Fashions of the Roaring Twenties. As Pictured in Sears and Other Catalogs, New York 1981, p. 56.

14 Seegers, Lu, Uhu, Koralle, Die Dame und Das Blatt der Hausfrau, in: Axel Springer Verlag (ed.), Presse- und Verlagsgeschichte im Zeichen der Eule. 125 Jahre Ullstein, Berlin 2002, p. 62-69, here pp. 59-60.

15 Osborn, Max, 50 Jahre Ullstein, Berlin 1927, p. 61; Ilgen, Volker, Sei sparsam Brigitte, nimm Ullstein-Schnitte!, in: Axel Springer Verlag (ed.), Presse- und Verlagsgeschichte im Zeichen der Eule. 125 Jahre Ullstein, Berlin 2002, pp. 54-61, here pp. 59-60.

16 Osborn, Ullstein, p. 60, as note 15.

17 Information based on full-page self-advertisement in the magazine Modenschau, no. 154 (12), October 1925, p. 44.